Design as Strategy?

Exploring the landscape of emerging Strategic Design practice

As I’ve journeyed deeper into my Masters of Design, I’ve explored a vast landscape of practice which focuses on how to intervene in complex challenges from the fuzzy front end of design (Sanders & Stappers [1]), where there is no brief — just an existing state with unmet potential.

The goal of my Masters of design is to identify and develop high impact ways to improve the social & environmental outcomes of environmental conservation projects.

I wanted to take this on because I deeply care about the state of the environment, and believe that more energy needs to be trained on these kinds of complex challenges. Previously I’ve trained my brain on areas as diverse as decentralised organising, youth mental health, and local food systems.

At the beginning of my Masters, I chose to address this challenge through what I termed a ‘Strategic Design lens’. Of course, my supervisors’ first provocation was “what do you mean by that?”. On examination, I realise my original orientation to Design was from a strategy and systems perspective, rather than an aesthetic design background, so I find my practice is stronger when starting from a wide field of enquiry.

What exists in this design landscape already?

It’s always worth taking a moment to pause to acknowledge the thinking and field building which has come before us. The first part of this series is a wayfinding exercise to develop a framing for Strategic Design activities, identify some of the common practice, and look at how it may result in different outcomes for a project.

Four Orders of Design

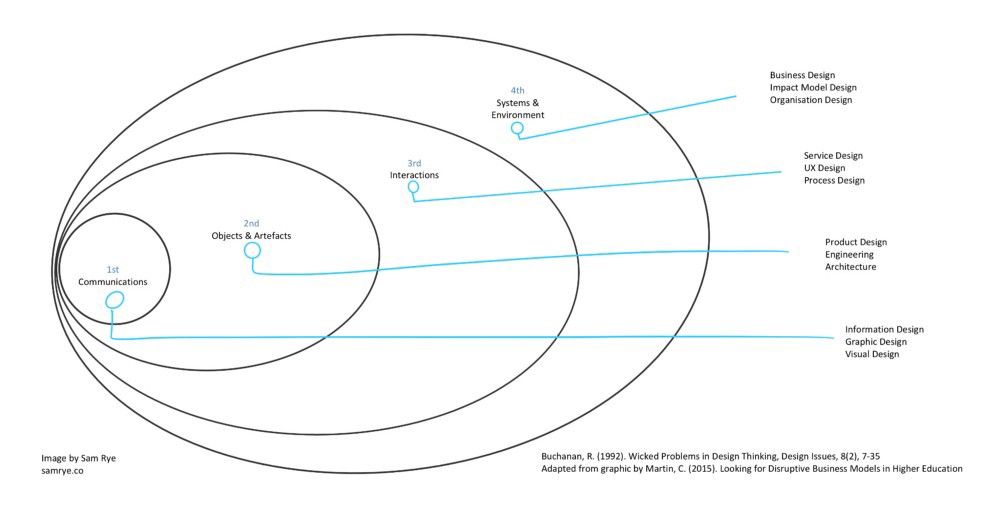

Richard Buchanan is often cited as an originator of the concept of the Four Orders of Design, which articulated the broadening landscape of design in his 1992 article Wicked Problems In Design Thinking [2].

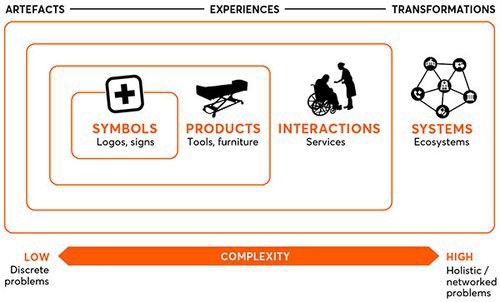

Buchanan’s work highlighted the emerging fourth order of design, which concerns itself mostly with the Systems & Environment. Whilst Buchanan doesn’t talk about this as Strategic Design, it does locate designers into a realm where challenges are inherently more complex (as referenced by Nesta’s adaptation of the above diagram in “What do we mean by design?” to show growing complexity as the orders expand [3].

Golsby-Smith argues in his 1996 article [4], that fourth order design is less about specific domains, and more about the way in which designers work and how they take accountability for the success (or failure) of their actions. He says “These attributes of purpose (culture), integration and system (community) provide the emerging subject matter for fourth order design” and adds that the Designer’s role is to widen the scope of enquiry to better achieve success:

“the fourth order designer moves the boundary of the task out to encompass the issues of “Why are we doing this task?” and, in answering this question,”What does it tell us about our identity and value?” Similarly, the fourth order designer also will move the scope of the task out to encompass connected systems and activities; to achieve integration so that the product does not operate as a fragment in the world, but within useful and viable patterns. Finally, the fourth order designer widens the scope of this practical task to include the people involved in creating and using the product (i.e., the product decisions are not taken in isolation; nor are they driven primarily by the creative lone voice of the designer; but are developed in discussion with a sense of growing purpose and commitment.”

A further discussion about the nature of design practice in ‘Oscillating Between Four Orders of Design’ [5] offers a useful case study of how initiatives require Designers to be multi-disciplinary and collaborative in their approach and the need to move fluidly between the different orders.

Given these critiques, I feel the orders of design should be thought of as permeable — whether it is as a design project expands in scope to recognise wider factors at play, or because of someone showing leadership to attempt to integrate strategic or cultural factors to increase the likelihood of success.Personally I find attempting to locate an initiative within these orders is a useful exercise as it sets intention about the scale and scope of an intervention.

Definitions

Several terms continue to surface as I look at this practice and associated disciplines. These definitions are only indicative as the landscape is emerging as design is applied to different domains and challenges.

Strategy

Firstly, I think it’s worth clarifying the much overused term “Strategy”.

I enjoy the seminal work by Professor Richard Rumelt who argues that most of what is presented as strategy, isn’t. Too often, strategy is confused for vision, goal setting and objectives.

“Good strategy almost always looks this simple and obvious and does not take a thick deck of PowerPoint slides to explain. It does not pop out of some “strategic management” tool, matrix, chart, triangle, or fill-in-the-blanks scheme. Instead, a talented leader identifies the one or two critical issues in the situation — the pivot points that can multiply the effectiveness of effort — and then focuses and concentrates action and resources on them.”

— Rumelt “Good Strategy Bad Strategy: the difference and why it matters [6]

Rumelt also differentiates between good and bad strategy:

“Good strategy is coherent action backed up by an argument, an effective mixture of thought and action with a basic underlying structure I call the kernel.”

Rumelt identifies the kernel of good strategy as:

- A diagnosis that defines or explains the nature of the challenge.

- A guiding policy for dealing with the challenge.

- A set of coherent actions that are designed to carry out the guiding policy.

Rumelt observes later in the book, when talking about one of his colleagues sitting in on his classes at UCLA “I noted that many of the lessons learned in a strategy course come in the form of the questions asked as study assignments and asked in class. These questions distill decades of experience about useful things to think about in exploring complex situations. John gave me a sidelong look and said, “It looks to me as if there is really only one question you are asking in each case. That question is ‘What’s going on here?’”.

This is important framing for strategic design exploration as without solid understanding of what makes good strategy, design practice is built on weak foundations.

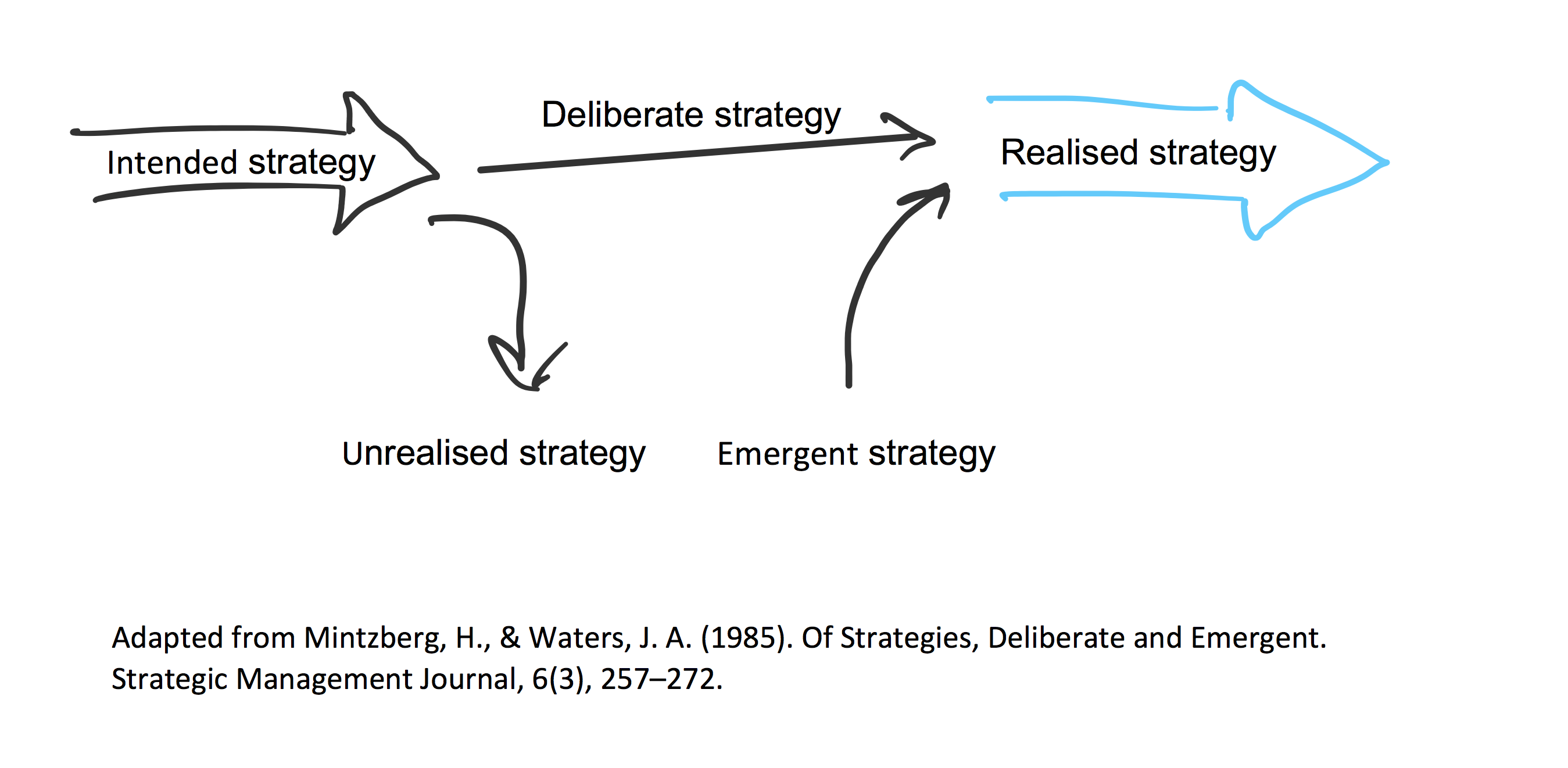

“Since strategy has almost inevitably been conceived in terms of what the leaders of an organization ‘plan’ to do in the future, strategy formation has, not surprisingly, tended to be treated as an analytic process for establishing long-range goals and action plans for an organization; that is, as one of formulation followed by implementation. As important as this emphasis may be, we would argue that it is seriously limited, that the process needs to be viewed from a wider perspective so that the variety of ways in which strategies actually take shape can be considered.”

— Mintzberg “Of Strategies, Deliberate and Emergent” [7]

Mintzberg’s articulation of strategy in this paper indicates some very useful directions for designers to match their approach with the circumstances in which they’re formulating strategies and associated solutions.

Strategic Design

Helsinki Design Lab “What is strategic design” [8]:

Traditional definitions of design often focus on creating discrete solutions — be it a product, a building, or a service. Strategic design is about applying some of the principles of traditional design to “big picture” systemic challenges like business growth, health care, education, and climate change. It redefines how problems are approached, identifies opportunities for action, and helps deliver more complete and resilient solutions.

Strategic design is about crafting decision-making.

Design Akademie Berlin “Strategic Design: Human-centered design for strategic innovations in society and companies”:

Design is not just about aesthetics. It has the potential to change the world and create sustainable companies. […] Strategic design represents the study of human behavior in context and latent, unmet needs and drive strategic value. Strategic designers study people’s implicit attitudes, behaviors and motivations to gain insight about their openness to consider something new. They use design thinking and design-specific skills to translate these insights into transformative products and services, and they serve as an important human-centered catalyst to help venture teams create the future. Strategic designers are adept at creating insightful venture opportunities and platforms, as well as compiling and analyzing ethnographic research and contextual design customer behaviors, pain points, needs and aspirations.

Dan Hill “Dark Matter and Trojan Horses: A Strategic Design Vocabulary” [9]:

Strategic design attempts to draw a wider net around an area of activity or a problem, encompassing the questions and the solutions and all points in between; design involves moving freely within this space, testing its boundaries in order to deliver definition of, and insight into, the question as much as the solution, the context as much as the artefact, service or product.

Call the context “the meta” and call the artefact “the matter”. Strategic design work swings from the meta to the matter and back again, oscillating between these two states in order to recalibrate each in response to the other.

Strategy Design

School of Systems Change | Forum For The Future “What are the capabilities we need for system change?”:

Design system change strategies and interventions. A good diagnosis does not always mean a good strategy. We need to use our understanding of the system dynamics to create design principles and models that help us plan and make choices about where and how to intervene.

Design Strategist

Diego Mazo “What a strategic designer* does.” [10]

The first skill of a strategic designer is to be able to analyse the user and the context, qualitative and quantitatively. This means observing the users, their behaviors and how they act within the context to understand their latent needs using an empathic approach. The understanding of the users will ensure that the strategy will match the different stakeholders in the most appropriate way. Designers are problem solvers. However, there are different levels of problem solving. Strategic designers target the highest cognitive level known as Fuzzy front end. This part of the process is where the guidelines are created: the plan to penetrate a market, how a company should be differentiated, how the launch of the product fits with the brand, etc. Every action that the company does has to be designed, and this is our task as strategic designers. I think our attitude towards problems is the first step to solve them, we are not scared, we feel confident in this situation.

Finally, we state that designers are the bridge between business and users, being this characteristic one of our strength. Great truth. But since some time ago, we have started to use some of the business skills such business modelling, product and brand management among others that give us the confidence to make decisions and control that the plan previously defined is been respected.

Transition Design

Terry Irwin “Transition Design: A Proposal for a New Area of Design Practice, Study, and Research, Design and Culture” [11]:

Transition Design is a proposition for a new area of design practice, study, and research that advocates design-led societal transition toward more sustainable futures. This reconception of entire lifestyles will involve reimagining infrastructures including energy resources, the economy and food, healthcare, and education. Transition Design focuses on the need for “cosmopolitan localism,” a lifestyle that is place-based and regional, yet global in its awareness and exchange of information and technology. Transition Designers would apply a deep understanding of the interconnectedness of social, economic, and natural systems and the Transition Design framework proposes four key areas in which narratives, knowledge, skills, and action can be developed.

Design for Social Innovation

Ezio Manzini “Making Things Happen: Social Innovation and Design” [12]

Social innovation is a process of change emerging from the creative re-combination of existing assets (from social capital to historical heritage, from traditional craftsmanship to accessible advanced technology), the aim of which is to achieve socially recognized goals in a new way.

[…]

design for social innovation […] is a constellation of design initiatives geared toward making social innovation more probable, effective, long-lasting, and apt to spread.

Rise of industry practice

Perhaps the greatest pace of strategic design practice development, is happening in ‘industry’, with agencies all over the world claiming strategic design as some or all of their work.

However there is also a growing number of strategic design practitioners active in other sectors, such as Aid & Development, and Government, which makes sense in the context of where many societal-scale complex problems are traditionally felt and acted on.

Notable industry inclusions:

Notable public and quasi-public sector examples:

https://openpolicy.blog.gov.uk/category/policy-lab/

MindLab DK (now closed - story here)

What is Strategic Design practice?

Strategic Design practice is made up of a wide range of activities, methods and tools, and is much less well articulated than the likes of Service Design.

On Mindset

Practice stems from the mindset and oncology which we inhabit and act from.

If we recognise fourth order design as focusing on complex systems, we should pay attention to the shifts designers may need to make in our worldview, in order to be effective designers.

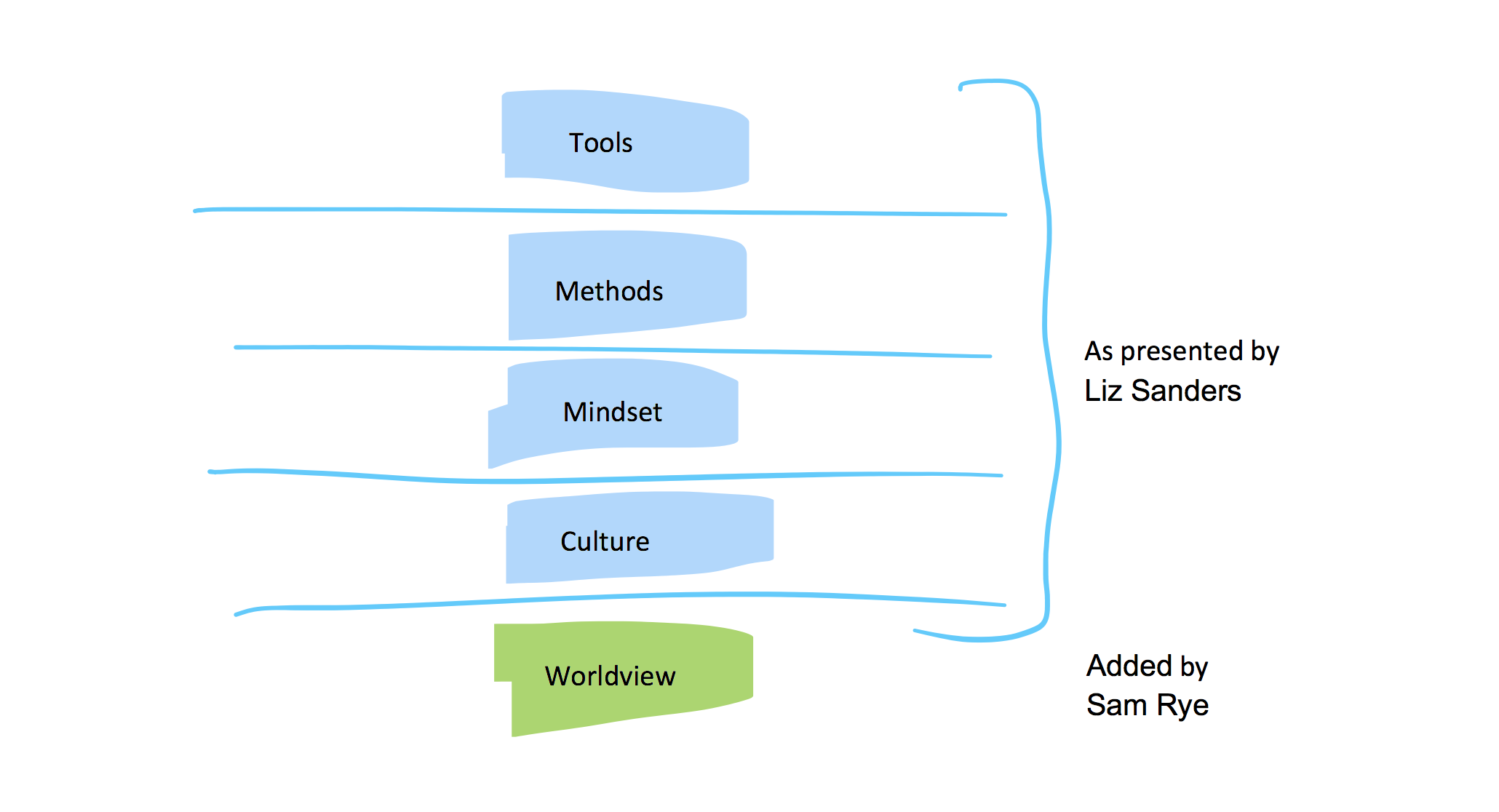

This diagram was introduced to me by Liz Sanders (Assoc Prof at Ohio State University), as a way of understanding how our Design practice is rooted in our culture [13]. I added ‘worldview’ below culture, as a deeper layer which drives our culture. Understanding things this way, we see that (some of) our existing methods and techniques developed in other orders of design may be inadequate for the reality of design work in fourth order.

Snowden offers us a sensemaking matrix, The Cynefin Framework. Beneath this framework (which helps people analyse the domain they are operating in), is the nuanced understanding of leadership and decision making which is appropriate; in short, it’s about appropriate strategy and mindset.

“Most situations and decisions in organizations are complex because some major change — a bad quarter, a shift in management, a merger or acquisition — introduces unpredictability and flux. In this domain, we can understand why things happen only in retrospect. Instructive patterns, however, can emerge if the leader conducts experiments that are safe to fail. That is why, instead of attempting to impose a course of action, leaders must patiently allow the path forward to reveal itself. They need to probe first, then sense, and then respond.”

— Dave Snowden, “A Leader’s Framework for Decision Making” [14]

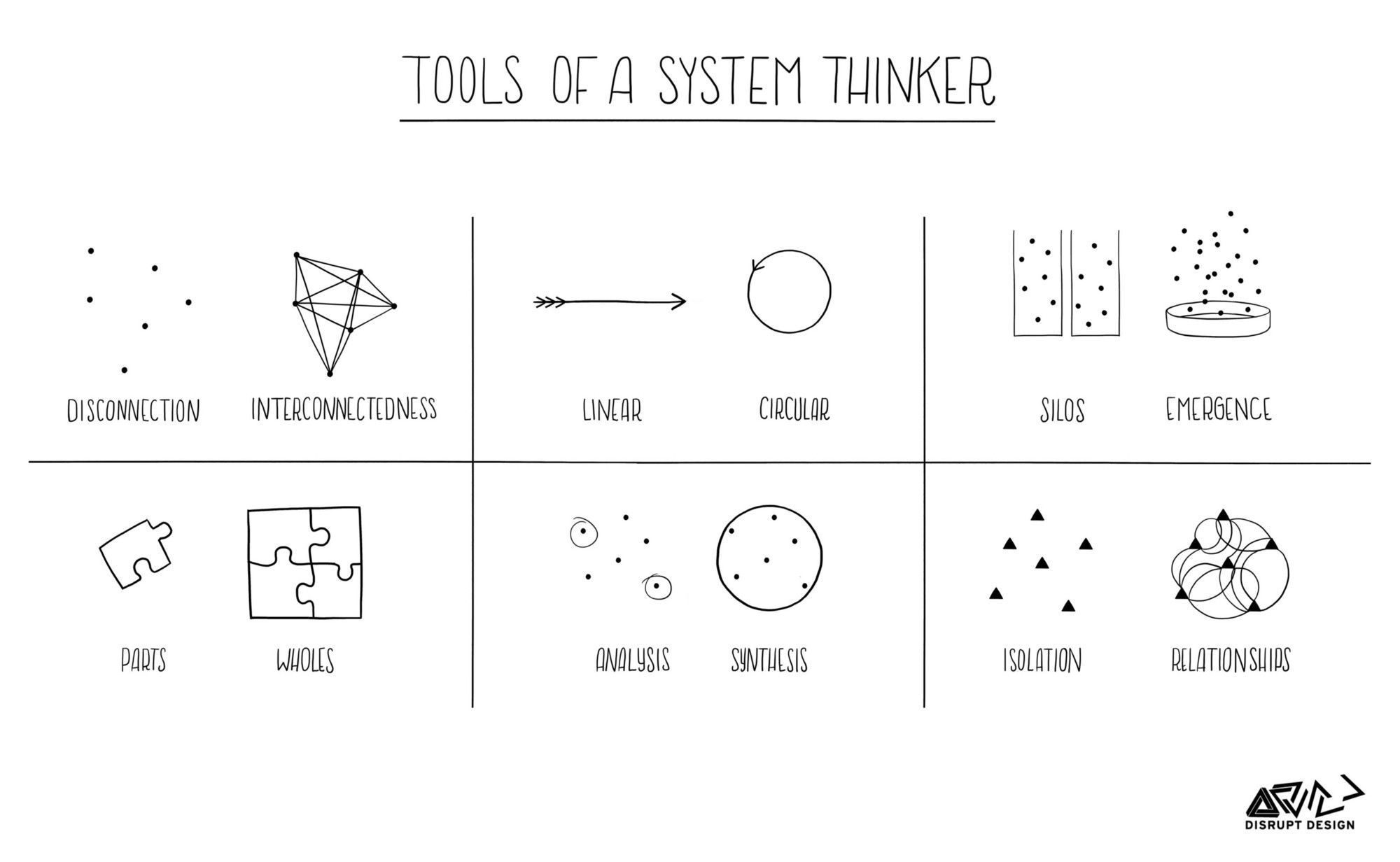

Looking at mindsets which allow people to work and thrive in complexity, Leyla Acaroglu introduces some concepts in ‘Tools of a Systems Thinker’ which all revolve a similar mindset — recognising and embracing interconnectedness. [15]

If we pair Sanders’ conceptualisation of the layers of design practice with Snowden’s overview of complexity science, and Acaroglu’s introduction of core concepts for systems thinking, we start to build a picture of the Mindset which designers working in the fourth order much inhabit.

On Activities

In an effort to explore what some bright minds thought about the practice, I kicked off a twitter thread. This lead to some interesting perspectives from a range of practitioners around the world. You can see the thread here:

Interested in your favoured perspectives or definitions of Strategic Design.

— Sam Rye (@sam__rye) July 17, 2018

Any offerings @johnthackara @jacwex @indy_johar @Kumeugirl @suhitanantula @emmablomkamp?

Perhaps my favourite was from John Thackara (Author and Designer at the intersection of social-ecological systems).

a) my perspective is that strategic design = design with purpose. Which all design is, except pointless design.

— john thackara 约翰·萨卡拉. (@johnthackara) July 17, 2018

b) definitions, by my definition, are what people do, who would otherwise busy themselves with pointless design.

I hope that helps.

The pragmatism of seeing Strategic Design simply as ‘what people do when they’re designing with purpose’, speaks to me. From my perspective, the value of defining a sub-discipline is largely to help people see themselves, to articulate why their work is important to them and others, and to solve common challenges one may face.

So, what do people do?

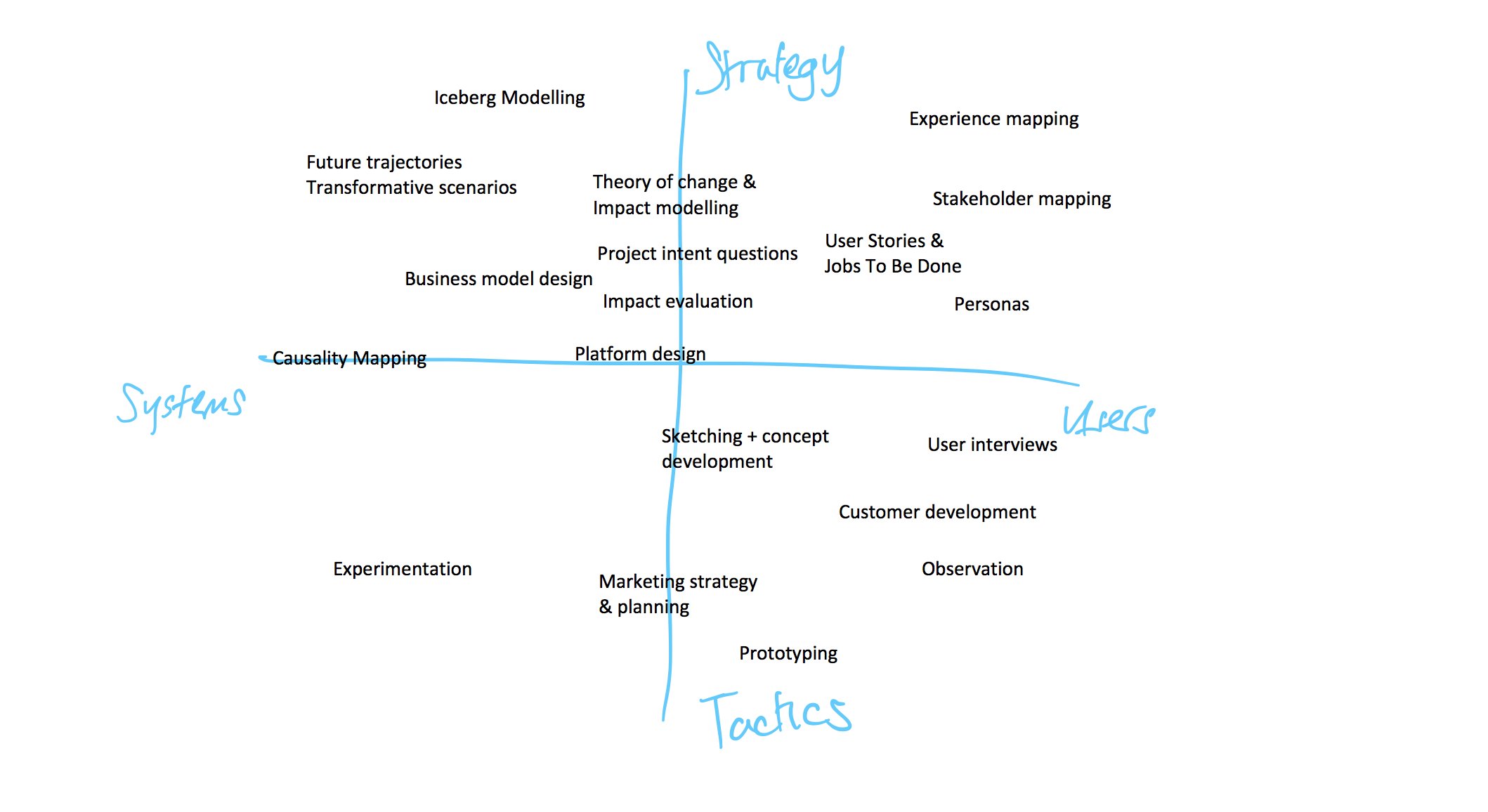

I thought I would broach this by sharing some of the activities I see when actively working on a project through a strategic design lens.

I mapped some of these onto a matrix to gain a little more insight about my own practice, and where the types of activities I tend to use, lie on the spectrums of Strategic-Tactical, and Systems-User-centered. I recognise that individual people are living systems (thus the spectrum isn’t literal), however I used more of a societal / ecological lens in this case. This raft of activities is by no means exhaustive — as John Thackara suggests, (strategic) designers will use whatever activities they need to build context, clarity and direction.

The main difference I observe between Design-centric activities and other disciplines which may operate in the fourth order or strategic realm, is the focus on making to understand (synthesis) instead of analysis-centric approaches.

Speaking of other actors in this realm, it is important to acknowledge a huge amount of work that has also been contributed by disciplines such as Social Sciences, Complexity Science, Facilitation and Social Process, Sustainability & Environmental Science, Futures, Movement Building, Collective Action.

Insights & Critique

What have we learned from all of this landscape exploration?

Insights

- Orders are permeable. It’s not really plausible to solely operate in the strategic end. Whilst there’s a lifetime of skills to acquire and evolve in strategy alone, truly successful design work will only come from understanding the entire process of value creation. Moving through the different orders, as necessary (and/or pulling in collaborators to help shine a light on blind spots), will create better outcomes.

- Activating the fuzzy front end. Whatever your definition, elevating Design to the strategic plane is really about allying creative approaches (typically associated with design) with the early stages of problem identification and framing, and enabling it to flow throughout the lifetime of the initiative.

- Mindset for thriving in complexity. I see an important pattern in recognising the types of mindsets and approaches which are best suited to the complexity inherent in fourth order design and strategic design practice. The key to me with this is firstly about the shift to a real understanding and familiarity with complex systems (characterised by interconnection and emergence), but also about why the types of thinking and sensemaking which are endemic to design — abductive thinking and synthesis — are so well suited to working in complexity.[16]

Critique

- Understanding Strategy. There is much misconception about what strategy actually is, and what denotes good strategy. Designers must go beyond integrative thinking and fully understand (good) strategy formation and action.

- Implications of acting in the fourth order. There are profound implications of acting at the fourth order of design, as the potential to shape society and ecology is significant. Some of the initial implications which come to mind, are about who is involved in the design work, what ethical standards are being applied, and how unintended consequences are addressed. Understanding the characteristics of complexity, and how our work as designers can operate within that context is important, as traditional planning-centric mindsets of linear cause-and-effect, are no longer relevant in the fourth order. Instead we must embrace a prototyping mindset and culture which offers better likelihood of success [17].

- Integrating Nature’s “voice”. Much of the strategic design practice I’ve seen talked about or highlighted in case studies, is a fierce proponent of human centered design. Yet all too often, our anthropocentric world doesn’t offer the best soil from which to grow truly sustainable solutions for our planet (see ethical implications, above). There’s a need for the strategic design field to investigate and share good practice when it comes to integrating all of nature as a stakeholder in our processes. If you’re interested in this, there’s an event series happening in August 2018 in Melbourne aimed at service designers.

Acknowledgements

A huge thank you to all the voices who chimed in on the twitter thread, including john thackara, Emma Blomkamp, Lee Ryan, Chris Jackson, Suhit Anantula, Alastair Somerville, Marc Rettig, Sophie Dennis, cameron tonkinwise, and anyone else I missed!

Also to inspiration from Indy Johar, Imandeep Kaur, Adam Groves, Tessy Britton, Liz Sanders, Andrea Siodmok, Lorna Prescott & Jo Orchard-Webb, amongst a wide field of others.

References

[1] Sanders, E. B.-N., & Stappers, P. J. (2012). Convivial toolbox : generative research for the front end of design. BIS. Retrieved fromhttp://www.bispublishers.com/convivial-design-toolbox.html

[2] Buchanan, R. (1992). Wicked Problems in Design Thinking. Design Issues, 8(2), 7–35. https://doi.org/10.2307/1511637

[3] Leurs, B., Roberts, I. (2017). What do we mean by design?. Nesta. Retrieved from https://www.nesta.org.uk/blog/what-do-we-mean-by-design/

[4] Golsby-Smith, T. (1996). Fourth Order Design : A Practical Perspective. Design Issues, 12(1), 5–25. Retrieved from https://www-jstor-org.ezproxy.massey.ac.nz/stable/pdf/1511742.pdf?refreqid=excelsior%3Aa73afb235eca91e89d4c6af5fa22a2e4

[5] Nylén, D., Holmström, J., & Lyytinen, K. (2014). Oscillating Between Four Orders of Design. Design Issues, 30(3), 53–65.https://doi.org/10.1162/DESI

[6] Rumelt, R. (2013). Good Strategy / Bad Strategy: the difference and why it matters. London: Profile Books Ltd. Retrieved from https://profilebooks.com/good-strategy-bad-strategy.html

[7] Mintzberg, H., & Waters, J. A. (1985). Of Strategies, Deliberate and Emergent. Strategic Management Journal, 6(3), 257–272. Retrieved from https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1002/smj.4250060306

[8] Helsinki Design Lab. (2018). What is strategic design? Retrieved fromhttp://www.helsinkidesignlab.org/pages/what-is-strategic-design

[9] Hill, D. (2014). Dark Matter and Trojan Horses: A Strategic Design Vocabulary. https://strelka.com/en/press/books/dark-matter-and-trojan-horses-a-strategic-design-vocabulary

[10] Mazo, D. (2016). What a strategic designer* does. Strategic Design Lab, (February 2014), 1–5. Retrieved from https://medium.com/strategic-design-lab/what-a-strategic-designer-does-b942f295379

[11] Irwin, T. (2015) Transition Design: A Proposal for a New Area of Design Practice, Study, and Research, Design and Culture, 7:2, 229–246, DOI: 10.1080/17547075.2015.1051829

[12] Manzini, E. (2015). Design, When Everybody Designs. (F. Ken & E. Stolterman, Eds.) (1st ed.). Cambridge: The MIT Press. Retrieved from https://mitpress.mit.edu/books/design-when-everybody-designs

[13] Sanders, L., & Stappers, P. J. (2012). Convivial design toolbox: generative research for the front end of design. BIS. Retrieved from http://www.bispublishers.com/convivial-design-toolbox.html

[14] Snowden, D. j., & Boone, M. E. (2007). A Leader’s Framework for Decision Making. Harvard Business Review, (November), 1–14. Retrieved from https://hbr.org/2007/11/a-leaders-framework-for-decision-making

[15] Acaroglu, L. (2017). Tools for Systems Thinkers: The 6 Fundamental Concepts of Systems Thinking. Disruptive Design, 1–8. Retrieved from https://medium.com/disruptive-design/tools-for-systems-thinkers-the-6-fundamental-concepts-of-systems-thinking-379cdac3dc6a

[16] Kolko, Jon (2010), “Abductive Thinking and Sensemaking: The Drivers of Design Synthesis”. In MIT’s Design Issues: Volume 26, Number 1 Winter 2010.

[17] Hassan, Z. (2015). The Rise of The Prototyping Paradigm. Social Kritik, 142, 1–13. Retrieved from http://www.socialkritik.dk/