The 'so what' of complexity - Part I

It's been the best part of 10 years I've been exploring and writing about complexity now - it's about time to capture some of the main learnings about the implications, rather than the substance.

I feel like it's been the best part of 10 years I've been exploring and writing about complexity now, and it feels about time to capture some of the main learnings about the implications, rather than the substance.

Practically speaking, what will we do differently and how, when we embrace complexity rather than fight it?

Reminder: most of my work focuses on developing strategies and experiments to influence change towards regenerative environmental and social outcomes, so that's the context for this post.

About Complexity

I'm not going into what complexity is, or what it means to have a complexity worldview. But here's a couple of quotes to frame the forthcoming fieldnote on what we do if we embrace the inherent complexity, rather than try to control, manage or fight against it.

Complexity theory challenges the dominant tradition of what is deemed ‘scientific’ and ‘professional’. It questions whether we can act as if the world behaves like a machine – is predictable, can be divided into parts, and defined by unambiguous cause-and-effect links. Complexity theory emphasises that the social and natural world is organic, systemic, shaped by history and context. Things are affected by many causes and connections and these act together, synergistically. The future emerges, cannot entirely be known in advance. What happens next is affected by history, chance, choice, and the particularity of the local context.

- Jean Boulton, Embracing Complexity (2015)

"But self-organizing, nonlinear, feedback systems are inherently unpredictable. They are not controllable. They are understandable only in the most general way. The goal of foreseeing the future exactly and preparing for it perfectly is unrealizable. The idea of making a complex system do just what you want it to do can be achieved only temporarily, at best. We can never fully understand our world, not in the way our reductionistic science has led us to expect. Our science itself, from quantum theory to the mathematics of chaos, leads us into irreducible uncertainty. For any objective other than the most trivial, we can’t optimize; we don’t even know what to optimize. We can’t keep track of everything. We can’t find a proper, sustainable relationship to nature, each other, or the institutions we create, if we try to do it from the role of omniscient conqueror."

- Donella Meadows, Dancing With Systems (circa 2000)

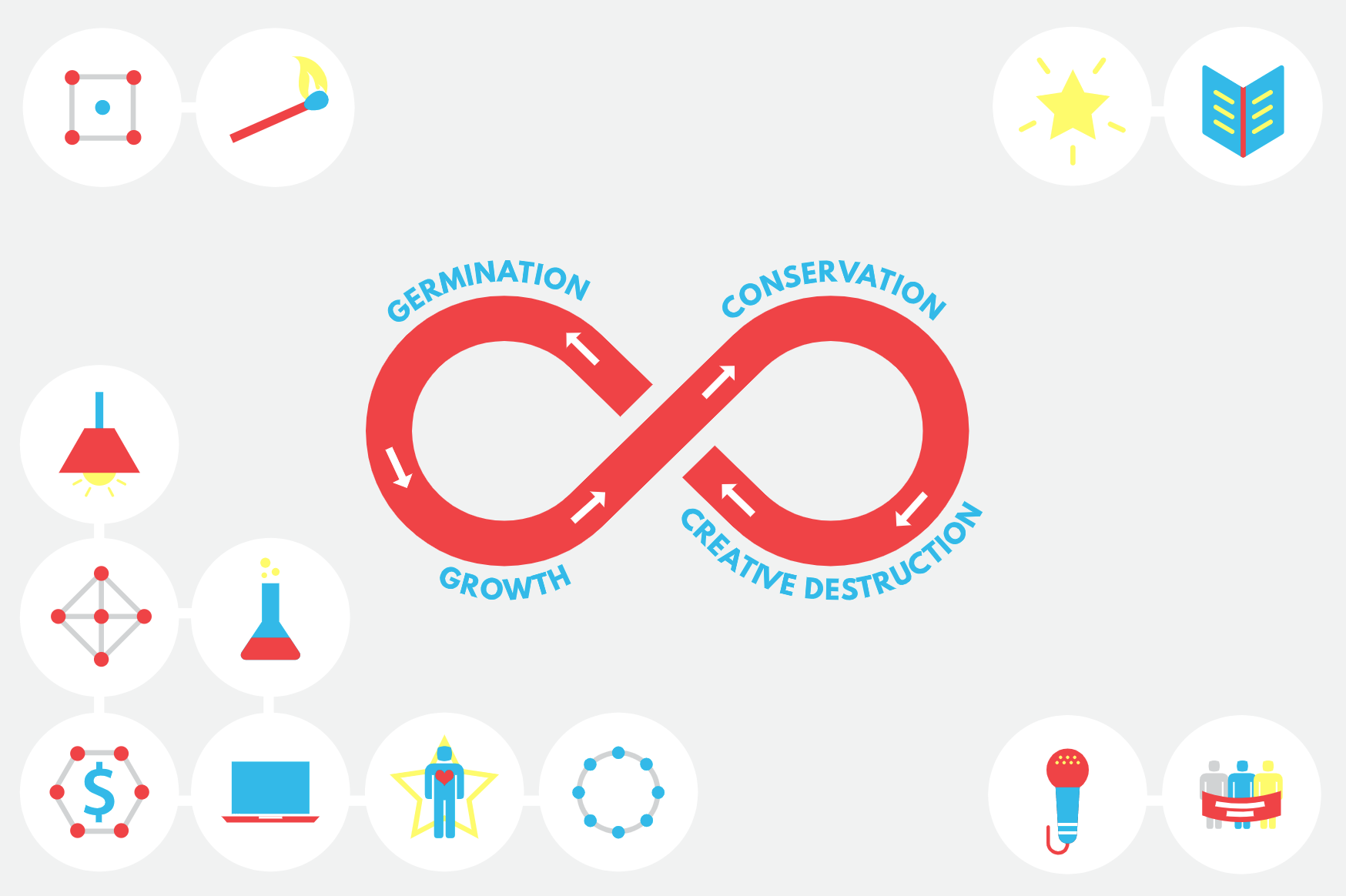

Adaptive Doing

The first, and biggest 'so what' for me is the shift in mindset from Planning (analyse-to-predict) to Experimentation (do-to-learn).

Whilst this doesn't always sound all that different, when you really take this idea that planning 3-5 years into the future isn't viable, because prediction is essentially a folly, then you begin to realise that it has to affect everything about the way many of us work and organise.

Covid-19 has introduced us to radical uncertainty and volatility. What seemed settled internation trade routes are suddenly severed. Families who live a state or two apart are unable to visit one another. Centralised national stockpiles of medicines are difficult to move around at speed. We are only just starting to learn what this kind of uncertainty is like when it comes to changes forced by climate change. This interconnection, these contexts and elements that make up small and large systems we've built our life around that are now coliding and affecting one another - this is the complexity inherent in all of our lives.

So can we predict the outcome of a new housing policy? The impact of implementing Universal Basic Income for a wealthy nation like Aotearoa New Zealand or Australia? The implications for mental health from one neighbourhood to another? Essentially - no. We can run all the models we like, but everything is essentially an experiment.

So what is this shift to Adaptive Doing about? It's about recongising everything is an experiment, and should be treated as such. Much as an expert navigator reads the landscape for signals, markers, seasonal changes and changes course - adaptation is about observation, evaluation, learning, and changing what we do based on these inputs.

This is counter to how most funding is structured for significant projects in the social, environmental and economic sphere (for example this recent paper on Power Dynamics in International Development by Cochrane - PDF link). Typically, a minimum of 1 year's funding is invested based on a planned "project logic" (based on assumptions and predictions), and little room is given for change in activities due to shifting context or real time evaluation. If you're funded to deliver a mental health service, and you identify during that time that there's a better way of delivering that service - you can't change what you're delivering until the end of the contract.

Around the world, we're investing the majority of our funds which are vital to deliver social & environmental outcomes, through mechanisms which actively work against the kind of rapid adaptation which is now necessary.

What is the alternative we need then?

We need to create organisations, teams, networks, and funding relationships which are practiced in adaptative doing.

The central characteristic of these types of individuals and entities is that they are learning-centric. They must research continuously - scanning new knowledge, engaging in internal and external communities of practice, invest in participatory design and evaluation to shape and re-shape their work.

Who are the people at the heart of these efforts? I quite like Rachel Sinha & Tim Draimin's take on this in Mapping Momentum from a little while ago - the roles they identified on the inside of change initiatives, making things happen.

The roles of Experimenter and Knowledge Builder resonate with the idea of Adaptive Doing - the driving forces that shape the culture of continuous learning, meaning making and course correction. Likewise, new roles created in the UNDP Accelerator Labs such as Head of Experimentation, Head of Exploration and Head of Solutions Mapping point toward a future of learning and adaptation.

Some tangible examples of these kinds of teams and organisations rooted in adaptation culture do exist, fear not - here's three quick examples...

Colab Dudley

Shout out to Lorna, Jo, and the amazing broader team who do an amazing job running a community-based social lab in Dudley, and sharing their learnings about the process. Their culture of curiousity, blending practices, and open accountability is refreshing and I'd like to see more of it.

Dark Matter Labs

A pioneer of so many ways of being, doing and thinking - DML have been provoking, agitating, and now clearly growing into some really exciting work over the last 5 or so years. With a deeply strategic and systemic approach to tackling big gnarly problems, I'm intrigued to know more about the culture that binds and drives the team.

UNDP Accelerator Labs & Regional Innovation Centre Asia-Pacific

Certainly having spoken with and followed some of the work from the teams within UNDP's Accelerator Labs and Regional Innovation Centre, it feels like a significant piece of work is happening to bring about a new culture, new practices, and focus UNDP towards learning at speed. Examples include this post, this one, and this one.

Complexity “is a middle ground theory between saying we know everything and we know nothing”. It's about learning to be comfortable with uncertainty, because inevitably things will not go according to our plan. We can adapt by becoming more resilient and refraining from our command and control methods.

- Human Current Podcast

To be continued

This piece suddenly became a long read in just the first part, so I've decided to break it up and will share more on the 'so what' of complexity in coming articles.

I'd love to hear from you on what you think are the most important shifts which need to be made, to embrace the complexity of the world and the challenges we face.

Now published in this series:

Part II which focuses on how I approach complex challenges and Part III which focuses on specific ways we can design change initiatives differently.